Function Apps: Dependency Injection and Auto Scaling

With the advent of serverless computing, we aim towards greater scalability, more flexibility, and quicker time to release, all at a reduced cost as compared to the traditional web services (not for everything though). Additionally, with .NET Core adding in-built support for dependency injection and the ability to be able to define the lifetime of an object (singleton, scoped or transient), with all the benefits it provides, we do not have default support for those with Azure Function Apps (serverless apps on Azure). Therefore, in this article, we would be looking into how we could leverage the goodness of dependency injections and scoping the created objects with Function Apps.

We could debate over the fact that serverless computing is expected to be small and short-lived without (m)any dependencies whereas we over here are talking about dependency injections and handling the lifetime of objects where they would expect to handle objects with every invocation. Actually, in Azure, the function apps have been designed to work on top of Azure Web Jobs/App Services, which is an Azure flavour for hosting traditional web services, therefore they support long-running workloads.

Function Apps can be hosted on either consumption (pay-as-you-go) plan or a fixed-cost plan with an App Service. Although both have their pros and cons the former allows for auto-scaling with a variable cost whereas the latter allows for long-running processes but with a fixed cost and resources. And based on this microsoft documentation, the azure function apps can scale up to 100 instances on Linux and run up to 10 mins at max if working with consumption plans. Therefore, will be exploring more towards hosting the application in a consumption plan.

Objectives

The objectives of this article are setting up the following:

- Sample function app

- Startup class and object lifetimes

- Observations after hosting in Azure

Implementation

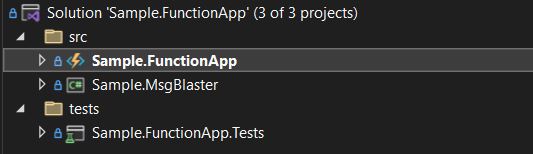

For the demo, we are going to set up a function app with .net 6.0 and a service-bus triggered system. Therefore, setting up a project structure with a function app to read messages, a message blaster to be able to push messages to the queue on service-bus and tests for the same.

You can access the entire code from my GitHub Repo

Setting Lifetime-based Services

To keep things simple, we are going to set up similar functionality in all the services via a BaseService and going to name the services based on their lifetime. We have added another service that requires all the other services to be able to observe the lifetime called ConsolidatedService.

Let’s set up the interfaces specifying the actions we wish to have, making those testable.

public interface IBaseService

{

void DoWork(ExecutionContext executionContext, string message = null);

}

With the help of this Interface, we now create 3 more interfaces namely, ISingletonService, IScopedService, ITransientService. The name of the interfaces signifies their lifetime scope:

- Singleton: New instance created once per application

- Scoped: New instance created once per invocation/call

- Transient: New instance created for every request

// Interfaces to specify one interface per lifetime scope

public interface ISingletonService : IBaseService

{

}

public interface IScopedService : IBaseService

{

}

public interface ITransientService : IBaseService

{

}

In addition to this, let’s also create an interface for the ConsolidatedService as follows:

public interface IConsolidatedService

{

void Execute(ExecutionContext executionContext);

}

Great! Now, since all the interfaces are set up let’s set up the classes and associated tests. Although I have written tests and completed this with TDD (Test Driven Development) in this article I will not be jumping into the unit tests aspect of it but rather just the application. Therefore, let’s look into setting up the BaseService.

internal abstract class BaseService : IBaseService

{

protected Guid Identifier { get; }

protected ILogger Logger { get; }

protected string ServiceName { get; }

protected BaseService(ILogger<IBaseService> logger)

{

this.Identifier = Guid.NewGuid();

this.Logger = logger;

this.ServiceName = this.GetType().Name;

this.Logger.LogInformation("Service Created:{0}||Id:{1}", this.ServiceName, this.Identifier);

}

public void DoWork(ExecutionContext executionContext, string message)

{

var finalMessage = "Function:{0}||InvocationId:{1}||Service:{2}-{3}||Id:{4}";

this.Logger.LogTrace(finalMessage, executionContext.FunctionName, executionContext.InvocationId, this.ServiceName, message, this.Identifier);

}

}

As we can observe in the base service, we provide a unique Identifier on object creation and log it as is. This would help us understand how the comes into the picture at the time of execution of the function app. Now, we can set up the rest of the scoped lifetime services pretty straightforwardly.

internal class SingletonService : BaseService, ISingletonService

{

public SingletonService(ILogger<IBaseService> logger) : base(logger)

{

}

}

internal class ScopedService : BaseService, IScopedService

{

public ScopedService(ILogger<IBaseService> logger) : base(logger)

{

}

}

internal class TransientService : BaseService, ITransientService

{

public TransientService(ILogger<IBaseService> logger) : base(logger)

{

}

}

Now, setting up the consolidated service which is dependent on the other services based on the interface setup above.

public class ConsolidatedService : IConsolidatedService

{

private readonly IScopedService scopedService;

private readonly ISingletonService singletonService;

private readonly ITransientService transientService;

public ConsolidatedService(ISingletonService singletonService, IScopedService scopedService, ITransientService transientService)

{

this.scopedService = scopedService;

this.singletonService = singletonService;

this.transientService = transientService;

}

public void Execute(ExecutionContext executionContext)

{

const string message = "ConsolidatedService";

this.scopedService.DoWork(executionContext, message);

this.singletonService.DoWork(executionContext, message);

this.transientService.DoWork(executionContext, message);

}

}

Setting up a Function App

In general, there would be no dependency injections in the function app, but now setting it up with the same.

public class SampleFunctionApp

{

private readonly IScopedService scopedService;

private readonly ISingletonService singletonService;

private readonly ITransientService transientService;

private readonly IConsolidatedService consolidatedService;

private readonly ILogger logger;

public SampleFunctionApp(ISingletonService singletonService, IScopedService scopedService, ITransientService transientService, IConsolidatedService consolidatedService, ILogger<SampleFunctionApp> logger)

{

this.scopedService = scopedService;

this.singletonService = singletonService;

this.transientService = transientService;

this.consolidatedService = consolidatedService;

this.logger = logger;

}

[FunctionName("ProcessServiceBusMessage")]

public void ProcessServiceBusMessage(

[ServiceBusTrigger(queueName: "%QueueName%", Connection = "QueueConnectionString")] string messageContent, Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.ExecutionContext executionContext)

{

scopedService.DoWork(executionContext, executionContext.FunctionName);

singletonService.DoWork(executionContext, executionContext.FunctionName);

transientService.DoWork(executionContext, executionContext.FunctionName);

consolidatedService.Execute(executionContext);

logger.LogTrace("Function:{0}||InvocationId:{1}||Message:{2}", executionContext.FunctionName, executionContext.InvocationId, messageContent);

Thread.Sleep(10000);

}

}

As we can notice in the constructor, we have added all the services as well as the consolidated service, which itself has all the services as dependencies. This would help us observe the life of an object and on the other hand, the function body contains the sleep function to delay the execution, so that we can observe the scaling in azure.

Setting up Startup.cs

Let’s create a class called Startup.cs to begin with. For this class to work as the startup we would need to inherit this by either IWebJobStartup or FunctionStartup. For this, we need to work with a extension class over the services which comes from the namespace Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;.

In addition to any of them, we would also need to decorate the class with the assembly attribute and pass it the startup class’ type. This is what does the magic and makes the startup class functional.

[assembly: FunctionsStartup(typeof(Sample.FunctionApp.Startup))]

namespace Sample.FunctionApp;

[ExcludeFromCodeCoverage]

internal class Startup : FunctionsStartup

{

public override void Configure(IFunctionsHostBuilder builder)

{

builder.Services.AddScoped<IConsolidatedService, ConsolidatedService>();

builder.Services.AddScoped<IScopedService, ScopedService>();

builder.Services.AddSingleton<ISingletonService, SingletonService>();

builder.Services.AddTransient<ITransientService, TransientService>();

}

}

Now, since the project is all set up, it should look something like this finally with all the classes, interfaces and projects.

Observations

Local Instance

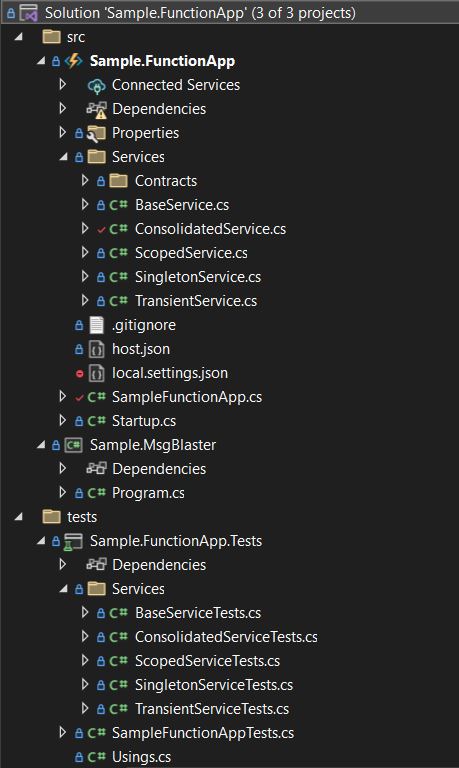

Running the function app locally and checking the logs for the same. Sent 2 messages one after the other manually to the service bus and we see the execution logs in the following manner:

From the executions above, we observe that there was only 1 singleton instance created and for each execution, there was 1 scoped instance created and a transient instance created for every request at the end of each scope we can see the message content being published, we can see that with the colour coding and the GUIDs associated with those. Therefore, what we learn from this is that function apps behave in the very same way that we work with any application respecting the dependencies.

Auto Scaling with Azure

Message Blaster

Now, hosting the function app in Azure on a Linux-based pay-as-you-go (Consumption) plan and utilizing the message blaster function to push 2000 messages to the service bus quickly.

public static void Main()

{

// Create Configuration

var configuration = new ConfigurationBuilder()

.AddUserSecrets<Program>()

.Build();

// Read from User Secrets

var connectionString = configuration["QueueConnectionString"].ToString();

var queueName = configuration["QueueName"].ToString();

// Create client and connections

var clientOptions = new ServiceBusClientOptions()

{

TransportType = ServiceBusTransportType.AmqpTcp

};

var client = new ServiceBusClient(connectionString);

var sender = client.CreateSender(queueName);

// Send messages and exit

try

{

Console.WriteLine("Started");

Parallel.For(0, 2000, new ParallelOptions() { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = 8 }, i =>

{

var msg = new ServiceBusMessage(Convert.ToString(i));

sender.SendMessageAsync(msg).GetAwaiter().GetResult();

});

Console.WriteLine("Completed");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex);

}

finally

{

sender.DisposeAsync().GetAwaiter().GetResult();

client.DisposeAsync().GetAwaiter().GetResult();

}

}

Scaling Services

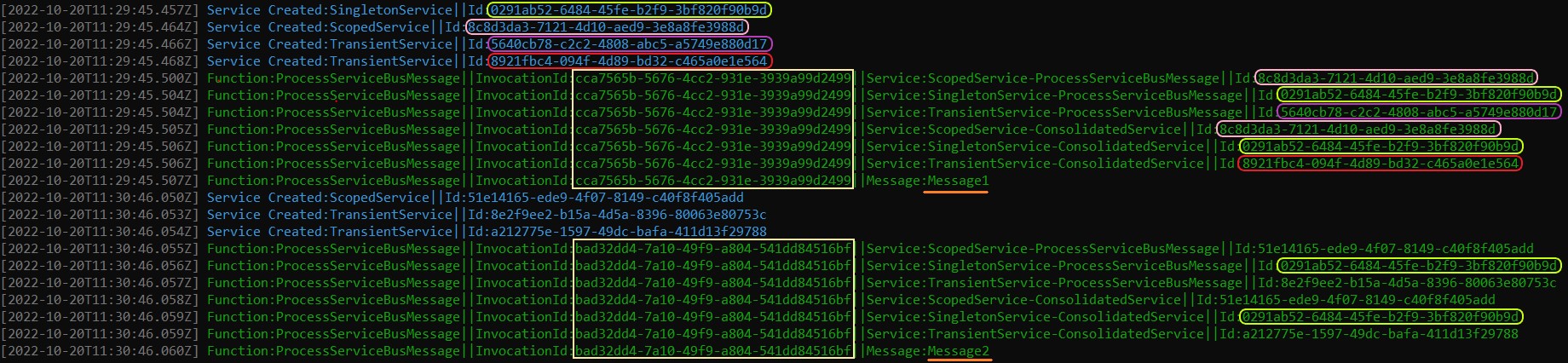

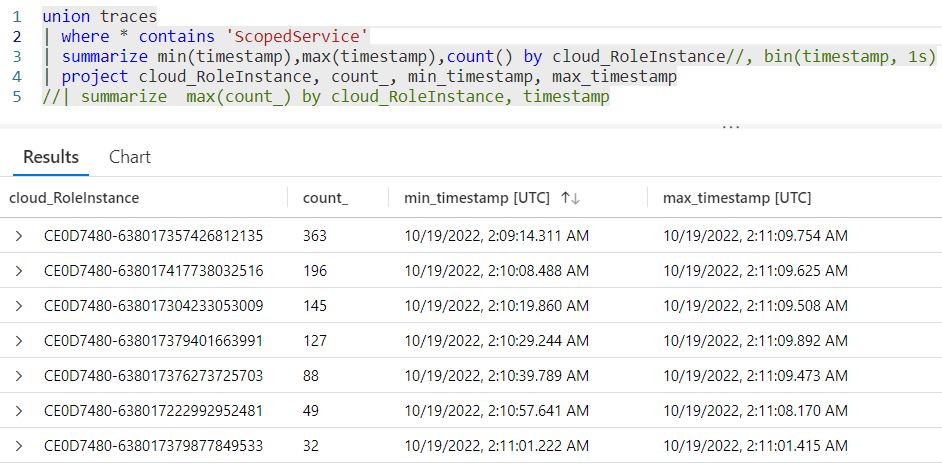

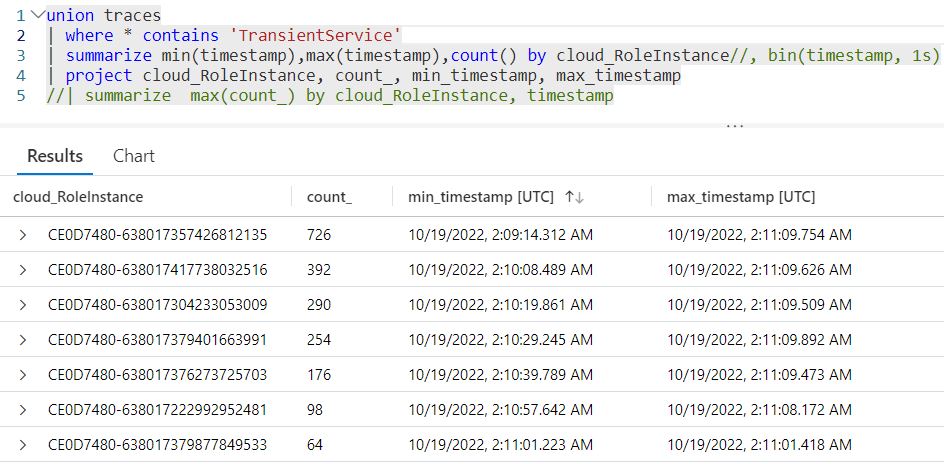

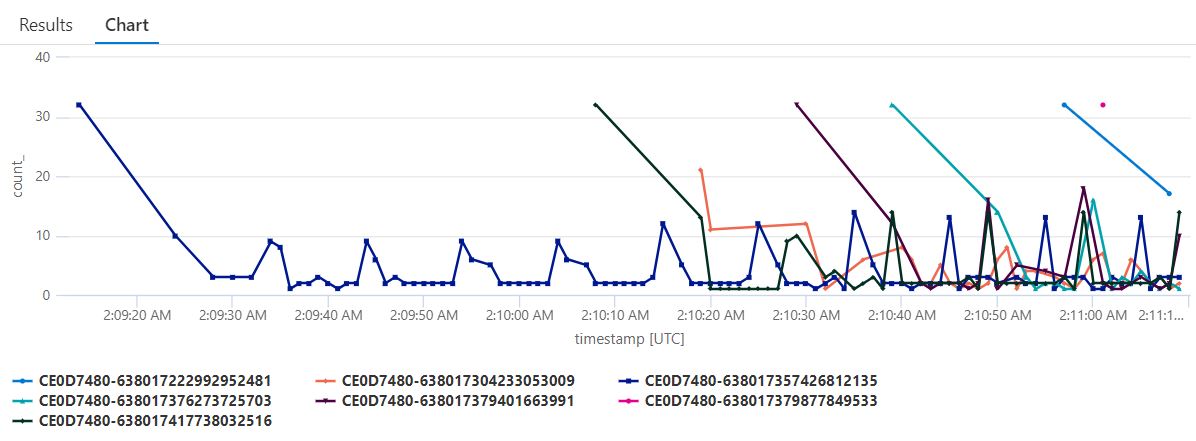

Once the messages got pushed into the queue, now analyzing the logs for the executions via application insights.

We observe that the function app scaled up to 7 instances to share the load on the service bus. We also observe that we see only 1 singleton service per instance; further since we sent 2000 messages in total, we see scoped service was created 2000 times and transient 4000 times as expected with the code overall.

Executions Per Second

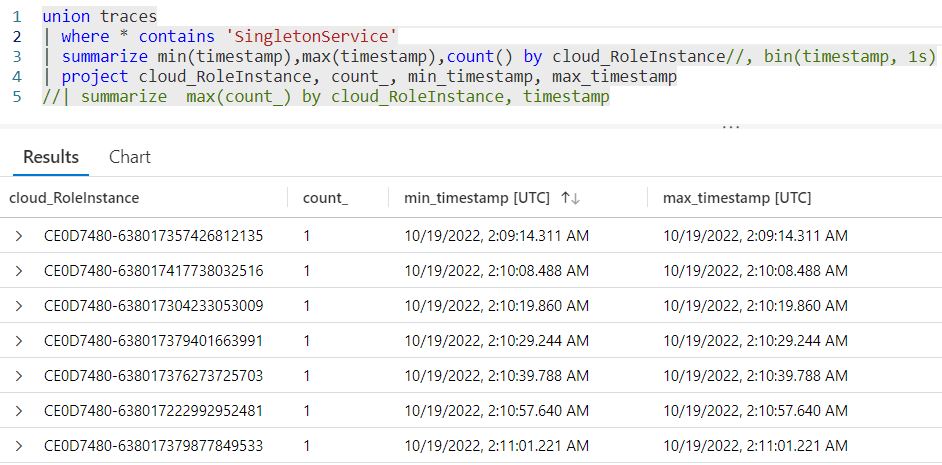

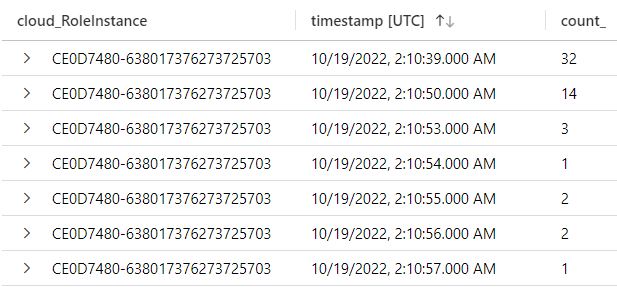

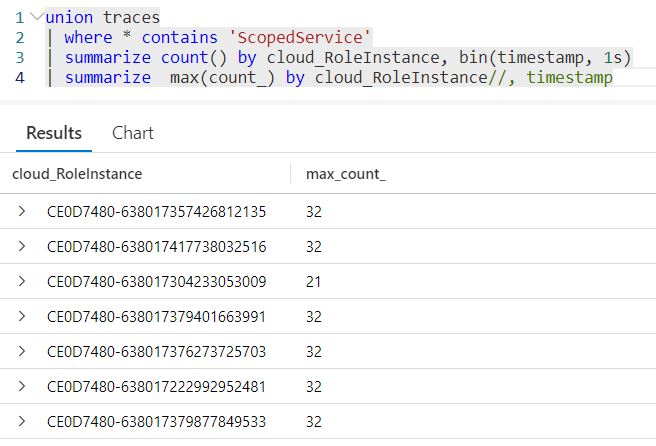

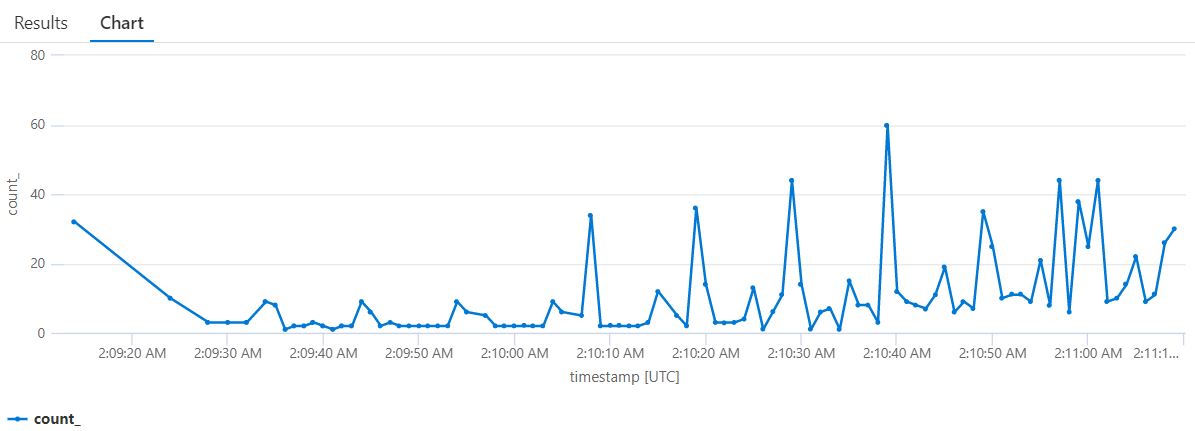

With the executions scaling with instances, let’s observe how many executions happened per second on one of the instances. Along with this where we see the executions per a single instance, looking at the max number of executions in any instance.

Graphically, the functions scaled up in the following manner (graphically):

The other way to look at it is the overall executions that happened irrespective of the instances:

Conclusions

We observed what we set out to do, basically setup a function app with dependency injections and then it auto-scaling when hosted on azure thereby adding another dimension on how we could create and host applications, based on our needs.

Comments